ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY IN SPHAKIA, CRETE

L. Nixon, J. Moody, S. Price, and O. Rackham, Echos du Monde Classique/Classical

Views 32 n.s.8 (1989) 201-15

We are most grateful to the Editor of Echos du Monde Classique/Classical

Views for permission to reproduce this article here

INTRODUCTION

The

second season of the Sphakia Survey was conducted in the summer of 1988.

Most of our time was spent on intensive survey of the Anopolis plain,

with some extensive work in other areas.1 The

second season of the Sphakia Survey was conducted in the summer of 1988.

Most of our time was spent on intensive survey of the Anopolis plain,

with some extensive work in other areas.1

The general objectives of the Survey are to investigate the environment

and vegetation of Sphakia; to clarify the nature and chronology of human

exploitation of the area; to determine when and how Sphakia was linked

with the outside world; and to study the stronghold effect in Sphakia,

which has resulted in marked preferences for inland rather than coastal

settlement locations in some periods.

The

pilot season of 1987 enabled us to work out a sampling programme suitable

for a research area of such generous size (the eparchy of Sphakia is circa

470 km2), based on eight environmental zones.2

Our specific objectives in 1988 were to investigate the mountain plain

of Anopolis in some detail and to continue the sampling of other environmental

zones, i.e. the foothills of the Araden area (up to 800m); middle slopes

(800-1200m) at Mouri; two more gorges, the Sphakiano and the Trypiti,

near whose mouth lies the site of Poikilasion ; and the coastal plain

at Frangokastello, where we could work with geologists studying the sedimentation

history of the area. We also wanted to visit sites in the adjacent eparchy

of Selino, to serve as comparison (Elyros, Hyrtakina, Lissos and Syia).

We were able to achieve all these objectives (and to clarify details of

the plan of Tarrha, at the foot of the Samaria Gorge); and to begin work

on an instructional video about the Sphakia Survey. The

pilot season of 1987 enabled us to work out a sampling programme suitable

for a research area of such generous size (the eparchy of Sphakia is circa

470 km2), based on eight environmental zones.2

Our specific objectives in 1988 were to investigate the mountain plain

of Anopolis in some detail and to continue the sampling of other environmental

zones, i.e. the foothills of the Araden area (up to 800m); middle slopes

(800-1200m) at Mouri; two more gorges, the Sphakiano and the Trypiti,

near whose mouth lies the site of Poikilasion ; and the coastal plain

at Frangokastello, where we could work with geologists studying the sedimentation

history of the area. We also wanted to visit sites in the adjacent eparchy

of Selino, to serve as comparison (Elyros, Hyrtakina, Lissos and Syia).

We were able to achieve all these objectives (and to clarify details of

the plan of Tarrha, at the foot of the Samaria Gorge); and to begin work

on an instructional video about the Sphakia Survey.

FIELD METHODS AND RECORDING

Nearly all fieldwork on the Sphakia Survey this year was done intensively,

by the systematic walking of transects.

Transects

During

the pilot season of 1987, one team of 4 walked "line" or "contour"

transects, designed to run through or cut across selected areas. In 1988,

we were aiming for more detailed coverage, particularly of the Anopolis

Plain, and therefore walked transects in selected 1 km squares. There

were two teams (A and B) of 3 or 4 people each, led by Nixon and Moody.

Members of each team walked in parallel, 10-15m apart. Each team could

cover 1/4 km2 per day, walking 5 N-S transects, 500m long and 50m wide,

with a 50m gap between them. Thus in 2 days, the survey could cover 1

km2. During

the pilot season of 1987, one team of 4 walked "line" or "contour"

transects, designed to run through or cut across selected areas. In 1988,

we were aiming for more detailed coverage, particularly of the Anopolis

Plain, and therefore walked transects in selected 1 km squares. There

were two teams (A and B) of 3 or 4 people each, led by Nixon and Moody.

Members of each team walked in parallel, 10-15m apart. Each team could

cover 1/4 km2 per day, walking 5 N-S transects, 500m long and 50m wide,

with a 50m gap between them. Thus in 2 days, the survey could cover 1

km2.

Walking transects in this manner requires a great deal of precision,

both in map-reading and in pace-counting. Our work this year was enormously

facilitated by the 1:5000 Greek Army maps, whose grid corresponds closely

to that of the more accessible 1:50,000 British Military maps. For that

reason we have used the co-ordinates of the latter maps to locate our

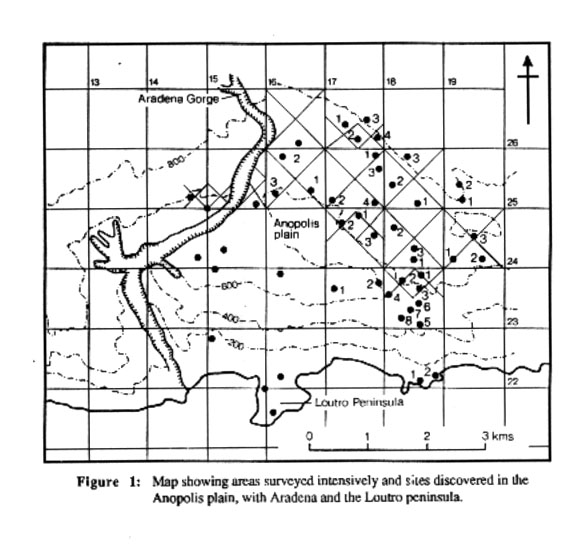

sites (e.g. 17/26.1 etc; see fig. 1). Compasses were necessary for accurate

navigation, especially in forested areas where sighting on a distant point

was impossible.

At the beginning of every transect, all members of a team recorded archaeological

and environmental information on their pace record forms. Every 50m, the

team would stop for an 'official' reading (10 per transect, 50 per 1/4

km2); in addition one team member would continue to record environmental

data on the environmental record form. 04.044 Initially, we also recorded

every artifact in between 'official' readings; later, we recorded only

diagnostic material between 50m readings. Brief comments were possible

on the pace record forms, but more detailed remarks, and 1/4 km2 and unit

summaries went on each team leader's transect comment form. When artifacts

were collected, they were placed in small self-sealing paper envelopes

or plastic bags with white plant labels, marked as follows: unit, team,

transect no., metres (or paces), recorder's initials, and date.

Recording

One

student stayed at home every day on a rotational basis, to input pace

record forms and environmental data on the computer, and to wash and label

finds. The 1988 finds have been bagged by team and transect, and arranged

in order by map unit. The 1987 finds have been labelled by area, transect

and pace, and bagged by date; thanks to the kindness of the Khania Museum,

we had last year's material with us throughout the 1988 season, which

made comparison between site collections much easier, especially for areas

that have now been visited several times. One

student stayed at home every day on a rotational basis, to input pace

record forms and environmental data on the computer, and to wash and label

finds. The 1988 finds have been bagged by team and transect, and arranged

in order by map unit. The 1987 finds have been labelled by area, transect

and pace, and bagged by date; thanks to the kindness of the Khania Museum,

we had last year's material with us throughout the 1988 season, which

made comparison between site collections much easier, especially for areas

that have now been visited several times.

Site definition

The

definition of the word "site" has often been a problem in survey

archaeology. For the Sphakia Survey, any locality with significant human

activity is a site. This flexible definition means that not all our sites

need be settlements; they could also be a set of ancient terraces; the

area round a spring in the White Mountains, and so forth. Our sites are

discovered in the field, often out loud, as the members of a team call

out their sherd densities. Because we survey areas where sites might not

be expected, and because we take readings every 50m, we can be fairly

certain that we know where sites are, and where they are not. (In most

of the areas covered so far, there seems to be very little background

noise.) When a site is diagnosed, a special collection of material may

often be made to include representative sherds for all fabrics and periods

observed plus stone tools, glass, etc. Short site summaries are included

on each team leader's transect comment sheets. Sites were then selected

for a revisit by both team leaders, at which point a detailed site record

form was filled out, and a general collection of artifacts to supplement

previous collections was made. Site recording also included photography

of the area, and of the finds. The

definition of the word "site" has often been a problem in survey

archaeology. For the Sphakia Survey, any locality with significant human

activity is a site. This flexible definition means that not all our sites

need be settlements; they could also be a set of ancient terraces; the

area round a spring in the White Mountains, and so forth. Our sites are

discovered in the field, often out loud, as the members of a team call

out their sherd densities. Because we survey areas where sites might not

be expected, and because we take readings every 50m, we can be fairly

certain that we know where sites are, and where they are not. (In most

of the areas covered so far, there seems to be very little background

noise.) When a site is diagnosed, a special collection of material may

often be made to include representative sherds for all fabrics and periods

observed plus stone tools, glass, etc. Short site summaries are included

on each team leader's transect comment sheets. Sites were then selected

for a revisit by both team leaders, at which point a detailed site record

form was filled out, and a general collection of artifacts to supplement

previous collections was made. Site recording also included photography

of the area, and of the finds.

This

year we also used a video camera and recorder.

Video has been used in excavations, but not, so far as we know, on surveys.3

The purpose of the video is to show our method of survey; to record sites

and different types of landscape; and to include ethnographic information

as necessary. This

year we also used a video camera and recorder.

Video has been used in excavations, but not, so far as we know, on surveys.3

The purpose of the video is to show our method of survey; to record sites

and different types of landscape; and to include ethnographic information

as necessary.

PERIOD RESULTS

i. Prehistoric Period (PH)

This is the period about which the least was known

before our Survey began, in terms of both the number and the distribution

of sites. Only six prehistoric sites had previously been identified in

Sphakia: the caves at Asphendou and Kapsodasos, plus two sites in the

Frangokastello Plain; Loutro; and a possible Mesolithic site found by

Mortensen in the Samaria Gorge. There were also the three Late Minoan

III vases from "ta pharangia" said to be from Sphakia.4

After

two seasons' work, we have located another 33 sites with PH material,

both on the coast (e.g. at Poikilasion and Khora Sphakion), and inland

(Livaniana, Mouri, and especially the plain of Anopolis). Thus there are

currently 39 sites with a PH phase, with material of this date found in

every region except the Madhares and Askyphou (though obsidian, usually

to be associated with earlier sites, has been found in the latter). After

two seasons' work, we have located another 33 sites with PH material,

both on the coast (e.g. at Poikilasion and Khora Sphakion), and inland

(Livaniana, Mouri, and especially the plain of Anopolis). Thus there are

currently 39 sites with a PH phase, with material of this date found in

every region except the Madhares and Askyphou (though obsidian, usually

to be associated with earlier sites, has been found in the latter).

While PH pottery is not usually difficult to recognise, PH sites can

be difficult to define and measure. The pottery is sometimes scattered

over large areas without a focus, presumably because it has been disturbed

in the Graeco-Roman and later periods.

The earliest PH material in Sphakia may come from Mortensen's site in

the Samaria Gorge, to which he assigns a tentative date of Epipalaeolithic

or Mesolithic; a Palaeolithic date has been given for the cave at Asphendou,

though later dates have also been suggested.

Stone tools

But

most of the PH material from Sphakia consists of pottery dating to Final

Neolithic/Early Minoan to Early Minoan, and stone tools. Though we do

find some ground tools, chipped stone is far more common: obsidian, including

at least one core; and chert, usually black or grey but in one instance

rose. Black chert occurs in abundance in Sphakia; grey chert also occurs

but less frequently. Obsidian occurs at nearly every site with a PH phase;

it obviously has to be imported, and is Melian in appearance. The tools

found in the survey have a wide range of specialised shapes; one site

alone produced at least 10 different types (Fig. 1, 18/24.1 = 4.53). But

most of the PH material from Sphakia consists of pottery dating to Final

Neolithic/Early Minoan to Early Minoan, and stone tools. Though we do

find some ground tools, chipped stone is far more common: obsidian, including

at least one core; and chert, usually black or grey but in one instance

rose. Black chert occurs in abundance in Sphakia; grey chert also occurs

but less frequently. Obsidian occurs at nearly every site with a PH phase;

it obviously has to be imported, and is Melian in appearance. The tools

found in the survey have a wide range of specialised shapes; one site

alone produced at least 10 different types (Fig. 1, 18/24.1 = 4.53).

Coarse ware chronology

Our

pottery dates are based on the coarse ware chronology developed in NW

Crete by Moody. The problem in W Crete generally is that painted decoration

on pottery is rarely preserved, with the exception of the mottle burnished

surface that dates the Final Neolithic/Early Minoan material (even when

the sherds are relatively small). Moody built up her coarse ware chronology

for the Akrotiri Peninsula by comparing surface finds with well-stratified

excavation deposits. The assemblages of fabrics found in Sphakia are sufficiently

close to those used by Moody to suggest that the rough outline of her

chronology can also be applied to Sphakia. One particularly good example

is an Middle Minoan fabric with calcareous temper found at the Anopolis

site mentioned above (photo row 3, 2nd sherd from left), which was already

known on the N coast from two excavated sites and Moody's survey.5 Our

pottery dates are based on the coarse ware chronology developed in NW

Crete by Moody. The problem in W Crete generally is that painted decoration

on pottery is rarely preserved, with the exception of the mottle burnished

surface that dates the Final Neolithic/Early Minoan material (even when

the sherds are relatively small). Moody built up her coarse ware chronology

for the Akrotiri Peninsula by comparing surface finds with well-stratified

excavation deposits. The assemblages of fabrics found in Sphakia are sufficiently

close to those used by Moody to suggest that the rough outline of her

chronology can also be applied to Sphakia. One particularly good example

is an Middle Minoan fabric with calcareous temper found at the Anopolis

site mentioned above (photo row 3, 2nd sherd from left), which was already

known on the N coast from two excavated sites and Moody's survey.5

It is fortunate for the Sphakia Survey that these coarse ware ceramic

parallels exist, as without them it would be difficult to date our finds

even in broad terms. But the presence in Sphakia of pottery fabrics similar

to those on the N coast (or possibly imported), and the amount of obsidian

found both suggest that the area was not totally cut off from the rest

of Crete, nor from the outside world.

Site location

The

choice of site location suggests that access to the sea (and its resources)

was often important. For example, 71% of the Frangokastello sites have

a PH phase (10 out of 14 sites so far), compared with only 27% of Anopolis

sites (11 out of 41 sites). This is not a function of exploration, as

we have now surveyed most of the upland Anopolis plain, with relatively

little time spent so far in the coastal area of Frangokastello. We also

found PH material, which includes a stirrup jar disc [now, 2000, thought

not to be a stirrup jar disc], at Poikilasion above the mouth of the Trypiti

Gorge (Profitis Ilias SW slopes 1.02 ).6 The

choice of site location suggests that access to the sea (and its resources)

was often important. For example, 71% of the Frangokastello sites have

a PH phase (10 out of 14 sites so far), compared with only 27% of Anopolis

sites (11 out of 41 sites). This is not a function of exploration, as

we have now surveyed most of the upland Anopolis plain, with relatively

little time spent so far in the coastal area of Frangokastello. We also

found PH material, which includes a stirrup jar disc [now, 2000, thought

not to be a stirrup jar disc], at Poikilasion above the mouth of the Trypiti

Gorge (Profitis Ilias SW slopes 1.02 ).6

It

is important to note, however, that there are PH - often early PH (Final

Neolithic/Early Minoan) - sites at inland and upland locations, e.g. Anopolis

and Aradena (Fig. 1, 18/23.5 = 4.44 and 14/25.1 = 3.16; and the tripod

foot from Mouri (6.02) (at c.1000m) suggests that the altitudinal range

for PH activity was broader than one might have expected. It

is important to note, however, that there are PH - often early PH (Final

Neolithic/Early Minoan) - sites at inland and upland locations, e.g. Anopolis

and Aradena (Fig. 1, 18/23.5 = 4.44 and 14/25.1 = 3.16; and the tripod

foot from Mouri (6.02) (at c.1000m) suggests that the altitudinal range

for PH activity was broader than one might have expected.

ii. Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods

After the Bronze Age there is little sign of human

occupation in Sphakia until the Classical period. Despite considerable

prosperity elsewhere on Crete in the Archaic period, there is Archaic

material from Sphakia only from graves at Tarrha.7

Four city states

But by the Classical/Hellenistic period there had emerged

four city states: Anopolis, Araden, Poikilasion and Tarrha; the names

of the first three, plus that of Phoinix, survive in modern toponyms.

There is Classical occupation known at Anopolis and Tarrha, and by the

Hellenistic period Anopolis, Araden and Tarrha were communities looking

outward to the wider Greek world. All three were signatories (along with

28 other Cretan states) to a treaty with Eumenes II of Pergamon in 183

B.C., and at around the same time all three sent sacred ambassadors (theoroi

) to Delphi; so too a theoros went from Apollonia, just east of our survey

area, to the Ptolemaia in Alexandria, where he died in 233 B.C.8

The

early Hellenistic period was, however, a time of turbulence. In the late

third century B.C. Anopolis was conquered by its enemies (perhaps Araden),

to receive liberation at the hands of Kharmadas, one of its own citizens.9

The earlier fortification wall at Anopolis probably dates to this period.

Poikilasion, whose Hellenistic location was first discovered by the Survey,

occupied a site of some physical inconvenience, some 400 metres above

the sea and higher than all the cultivable land . Such defensiveness reflects

the general prevalence of wars and of piracy in the period. Indeed, many

Cretans themselves served as mercenaries in the armies of the Hellenistic

kings. Kharmadas, the liberator of Anopolis, served in the Ptolemaic army,

and died at Gaza. The

early Hellenistic period was, however, a time of turbulence. In the late

third century B.C. Anopolis was conquered by its enemies (perhaps Araden),

to receive liberation at the hands of Kharmadas, one of its own citizens.9

The earlier fortification wall at Anopolis probably dates to this period.

Poikilasion, whose Hellenistic location was first discovered by the Survey,

occupied a site of some physical inconvenience, some 400 metres above

the sea and higher than all the cultivable land . Such defensiveness reflects

the general prevalence of wars and of piracy in the period. Indeed, many

Cretans themselves served as mercenaries in the armies of the Hellenistic

kings. Kharmadas, the liberator of Anopolis, served in the Ptolemaic army,

and died at Gaza.

Leagues

Such strife and insecurity was counterbalanced by the

formation of political leagues. In the fourth and third centuries B.C.

the Oreioi included Tarrha and Poikilasion with three cities further west,

Elyros, Hyrtakina and Lissos; between c.280 and 250 B.C. the Oreioi formed

an alliance with the king of Cyrene, the oath being by the deities of

Lissos and Poikilasion and other deities. In the mid-third century B.C.

a federation of Cretan cities came into existence, and formed the basis

for the signing of the treaty with Eumenes II.10

The coming of the Romans in the first century B.C. marked the end of overt

strife and insecurity within the island.

Such strife and insecurity was counterbalanced by the

formation of political leagues. In the fourth and third centuries B.C.

the Oreioi included Tarrha and Poikilasion with three cities further west,

Elyros, Hyrtakina and Lissos; between c.280 and 250 B.C. the Oreioi formed

an alliance with the king of Cyrene, the oath being by the deities of

Lissos and Poikilasion and other deities. In the mid-third century B.C.

a federation of Cretan cities came into existence, and formed the basis

for the signing of the treaty with Eumenes II.10

The coming of the Romans in the first century B.C. marked the end of overt

strife and insecurity within the island.

Prosperity

The

prosperity of the area in the Hellenistic and Roman periods is difficult

to assess. The surviving stonework shows no sign of ashlar construction,

which contrasts with other sites of the same period on Crete (such as

neighbouring Lissos) and elsewhere in the Greek world. The main local

limestone (Plattenkalk) is unsuitable for squared blocks, and only a limited

amount of other stone was brought in to make good the deficit (as, for

example, at the main site at Anopolis). There are also few monumental

civic buildings. There was a temple at Tarrha and perhaps two at Poikilasion

(one of the latter quite small),11 but

none of the four towns is known to have had a theatre, odeion, stoa or

even agora. Parts of columns have been found at Anopolis and Araden, but

they could be either Hellenistic-Roman or Byzantine, and are too small

to have been load-bearing. This contrasts with the remains of Roman theatres

at Elyros and Lissos, and the lavish architecture and sculpture revealed

by excavation at Lissos.12 The

prosperity of the area in the Hellenistic and Roman periods is difficult

to assess. The surviving stonework shows no sign of ashlar construction,

which contrasts with other sites of the same period on Crete (such as

neighbouring Lissos) and elsewhere in the Greek world. The main local

limestone (Plattenkalk) is unsuitable for squared blocks, and only a limited

amount of other stone was brought in to make good the deficit (as, for

example, at the main site at Anopolis). There are also few monumental

civic buildings. There was a temple at Tarrha and perhaps two at Poikilasion

(one of the latter quite small),11 but

none of the four towns is known to have had a theatre, odeion, stoa or

even agora. Parts of columns have been found at Anopolis and Araden, but

they could be either Hellenistic-Roman or Byzantine, and are too small

to have been load-bearing. This contrasts with the remains of Roman theatres

at Elyros and Lissos, and the lavish architecture and sculpture revealed

by excavation at Lissos.12

Settlement system

The

settlement system of the area has been much clarified by the survey, and

will be further illuminated once study of pottery enables a proper distinction

to be drawn between Hellenistic and Roman wares. There seems to be a change

in the khora/skala relationship between the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

The main site of Poikilasion, where we observed no pottery later than

the Hellenistic period, was perhaps abandoned in favour of the more congenial

setting of the Trypiti gorge. And the importance of Phoinix as the port

for Anopolis and Araden probably increased in the Roman period. But unlike

examples of change elsewhere on Crete, when the inland city declined in

favour of the port, Araden and Anopolis remained vigorous throughout the

Roman period.13 The

settlement system of the area has been much clarified by the survey, and

will be further illuminated once study of pottery enables a proper distinction

to be drawn between Hellenistic and Roman wares. There seems to be a change

in the khora/skala relationship between the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

The main site of Poikilasion, where we observed no pottery later than

the Hellenistic period, was perhaps abandoned in favour of the more congenial

setting of the Trypiti gorge. And the importance of Phoinix as the port

for Anopolis and Araden probably increased in the Roman period. But unlike

examples of change elsewhere on Crete, when the inland city declined in

favour of the port, Araden and Anopolis remained vigorous throughout the

Roman period.13

Anopolis

Within

the territory of Anopolis the survey has identified 35 out of 41 sites

(85%) as Hellenistic-Roman, which is the most common of all periods; intensive

survey has not so far been carried out on the territories of Araden, Poikilasion

or Tarrha. On the Anopolis plain, in addition to the main site of ancient

Anopolis (Fig.1, 17/23.1 = 4.21; ), our finds suggest two types of habitation

sites: small hamlets of a few houses; and isolated farms. Both are scattered

across the whole territory of Anopolis, often on south-facing slopes,

on slight rises in the plain and at heights of up to 800 m. The precise

dating of these sites is not yet possible, but one may note that outside

Anopolis there is very little black glazed pottery (e.g. Fig.1, 17/25.2

= 4.28), and that is found at the larger sites; while in the Roman period

Samian is found very widely, even at smaller sites (e.g. Fig.1, 18/23.2

= 4.41, 19/25.1 = 4.67). Within

the territory of Anopolis the survey has identified 35 out of 41 sites

(85%) as Hellenistic-Roman, which is the most common of all periods; intensive

survey has not so far been carried out on the territories of Araden, Poikilasion

or Tarrha. On the Anopolis plain, in addition to the main site of ancient

Anopolis (Fig.1, 17/23.1 = 4.21; ), our finds suggest two types of habitation

sites: small hamlets of a few houses; and isolated farms. Both are scattered

across the whole territory of Anopolis, often on south-facing slopes,

on slight rises in the plain and at heights of up to 800 m. The precise

dating of these sites is not yet possible, but one may note that outside

Anopolis there is very little black glazed pottery (e.g. Fig.1, 17/25.2

= 4.28), and that is found at the larger sites; while in the Roman period

Samian is found very widely, even at smaller sites (e.g. Fig.1, 18/23.2

= 4.41, 19/25.1 = 4.67).

Some

evidence for agricultural practice are the terraces within the Anopolis

plain and elsewhere in the survey area where a general scatter of Graeco-Roman

pottery might suggest cultivation in this period (e.g. Fig.1, 16/26.1

= 4.17). This evidence joins the other, very limited, evidence for the

use of terrace walls in the Greek world.14 Some

evidence for agricultural practice are the terraces within the Anopolis

plain and elsewhere in the survey area where a general scatter of Graeco-Roman

pottery might suggest cultivation in this period (e.g. Fig.1, 16/26.1

= 4.17). This evidence joins the other, very limited, evidence for the

use of terrace walls in the Greek world.14

Connections

The

connections between Sphakia and other parts of Crete and other parts of

the Mediterranean in the Hellenistic-Roman period require investigation.

There may be evidence of Hellenistic-Roman activity at a site in the Madhares;

and some Sphakiote personal names are peculiar to West Crete, which may

suggest links to the north coast.15 Pottery

offers the most systematic evidence that the area was tied to other parts

of the Mediterranean. At some point a 4th c. Attic red figure vase was

brought to the Frangokastello area,16 while in the Roman period pottery

was imported from Italy and North Africa, and a grain ship plying from

Alexandria to Rome once gained safety in the harbour of Phoinix.16

To what extent this part of the south coast gained substantially in prosperity

in the Roman period through trade remains to be seen. But the range of

non-Cretan pottery used in Sphakia does suggest that the area was linked

to the broader Mediterranean economy. The

connections between Sphakia and other parts of Crete and other parts of

the Mediterranean in the Hellenistic-Roman period require investigation.

There may be evidence of Hellenistic-Roman activity at a site in the Madhares;

and some Sphakiote personal names are peculiar to West Crete, which may

suggest links to the north coast.15 Pottery

offers the most systematic evidence that the area was tied to other parts

of the Mediterranean. At some point a 4th c. Attic red figure vase was

brought to the Frangokastello area,16 while in the Roman period pottery

was imported from Italy and North Africa, and a grain ship plying from

Alexandria to Rome once gained safety in the harbour of Phoinix.16

To what extent this part of the south coast gained substantially in prosperity

in the Roman period through trade remains to be seen. But the range of

non-Cretan pottery used in Sphakia does suggest that the area was linked

to the broader Mediterranean economy.

Late Roman period

Most of the sites occupied under the earlier empire seem to have continued

in use in the later Roman/First Byzantine period. The area of major expansion

was the Frangokastello plain, where the earliest post-Minoan evidence

for occupation (apart from the red figure vase already mentioned) is mid-third

century A.D. and where settlement became more dense in the fifth and sixth

centuries A.D. Why this area was apparently not settled earlier in the

Roman empire is at present unclear.

The

most notable architectural, and social, development was the building of

Christian churches in the fifth and sixth centuries at four sites: Araden;

Phoinix (at least two); Tarrha ; and on the Frangokastello plain at Ag.

Efstratios and Ag. Niketas. All these churches were larger than their

replacements in the second Byzantine period. The one site notably missing

from this list is Anopolis, where there is no clear sign of an early basilica.

And the one bishopric in Sphakia was based not on Anopolis but on Araden/Phoinix.

We cannot yet explain why Anopolis should have given ground to its neighbour

and rival Araden. The

most notable architectural, and social, development was the building of

Christian churches in the fifth and sixth centuries at four sites: Araden;

Phoinix (at least two); Tarrha ; and on the Frangokastello plain at Ag.

Efstratios and Ag. Niketas. All these churches were larger than their

replacements in the second Byzantine period. The one site notably missing

from this list is Anopolis, where there is no clear sign of an early basilica.

And the one bishopric in Sphakia was based not on Anopolis but on Araden/Phoinix.

We cannot yet explain why Anopolis should have given ground to its neighbour

and rival Araden.

As

a result of the Sphakia Survey, we now know the correct site of Hellenistic

Poikilasion; at Tarrha, we know that the city walls were for protection

against the sea (rather than fortification), which has implications for

Hellenistic and Roman sea levels. In the territory of Anopolis we have

found imported Samian and African pottery even at remote sites, which

would be very unusual in mainland Greece, and we are in a good position

to analyse the settlement hierarchy of an ancient city state. As

a result of the Sphakia Survey, we now know the correct site of Hellenistic

Poikilasion; at Tarrha, we know that the city walls were for protection

against the sea (rather than fortification), which has implications for

Hellenistic and Roman sea levels. In the territory of Anopolis we have

found imported Samian and African pottery even at remote sites, which

would be very unusual in mainland Greece, and we are in a good position

to analyse the settlement hierarchy of an ancient city state.

iii. Byzantine, Venetian and Turkish Periods (A.D. 962-1900)

Settlement in 19th and 20th c. Sphakia was of two types: "nucleated"

villages of the type familiar from other parts of Greece (e.g. Agios Ioannis,

Kapsodasos); and "dispersed" villages made up of several neighbourhoods

or hamlets (e.g. Anopolis, with 9; and Askyphou, with 5). Dispersed villages

occur elsewhere on Crete, especially in the W, but are otherwise rare

in modern Greece.

Villages

It

is likely that this pattern of settlement goes far back into the last

millennium, possibly to the Second Byzantine period (from the departure

of the Arabs in 962 to the Genoese (and then Venetian) takeover of Crete

in 1204). There is no evidence of any other settlement pattern, either

from the work of the Sphakia Survey, or from earlier studies.17

While all settlements in Sphakia have been depopulated, there are relatively

few earlier desertions before this century. We know of only one village

abandoned well before 1900, but still having standing ruins: the area

now known as Peradoro in the Trypiti Gorge, reported by Spratt in the

1850s, when it was already long deserted and nameless.18

And to date we have discovered only two other mediaeval habitation sites

outside villages, represented by sherd scatters and building foundations,

near Anopolis (Fig. 1,18/24.3 = 4.54) and Khora Sphakion. It

is likely that this pattern of settlement goes far back into the last

millennium, possibly to the Second Byzantine period (from the departure

of the Arabs in 962 to the Genoese (and then Venetian) takeover of Crete

in 1204). There is no evidence of any other settlement pattern, either

from the work of the Sphakia Survey, or from earlier studies.17

While all settlements in Sphakia have been depopulated, there are relatively

few earlier desertions before this century. We know of only one village

abandoned well before 1900, but still having standing ruins: the area

now known as Peradoro in the Trypiti Gorge, reported by Spratt in the

1850s, when it was already long deserted and nameless.18

And to date we have discovered only two other mediaeval habitation sites

outside villages, represented by sherd scatters and building foundations,

near Anopolis (Fig. 1,18/24.3 = 4.54) and Khora Sphakion.

Villages of both types (nucleated and dispersed) are distributed wherever

there is cultivable land. The highest village is Mouri (6.02) (now deserted)

at ca 1000m, where Byzantine/Venetian material has been found. We have

seen no agricultural terraces higher than 1000-1100m, but up to this altitude

almost every slope with even a little soil has been terraced. The presence

of numerous threshing floors suggests that the main crop was grain. It

is unfortunate that terraces are so difficult to date, so that we cannot

say definitely which (if any) areas were newly terraced in the second

Byzantine period.

Coastal settlement

Though

there is cultivable land by the sea in Sphakia, the coast was conspicuously

lacking in settlement through the 1000 years from the late Roman period/first

Byzantine period up to the age of tourism. Settlements are sometimes located

1 km or so inland, but are not directly visible from the sea; examples

are the deserted Trypiti village at Peradoro, and Agia Roumeli (the old

village). Avoidance of coastal locations is usually attributed to insecurity;

as late as 1867 eastern Sphakiotes did not live on the Frangokastello

plain because they feared raids from the sea.19 Though

there is cultivable land by the sea in Sphakia, the coast was conspicuously

lacking in settlement through the 1000 years from the late Roman period/first

Byzantine period up to the age of tourism. Settlements are sometimes located

1 km or so inland, but are not directly visible from the sea; examples

are the deserted Trypiti village at Peradoro, and Agia Roumeli (the old

village). Avoidance of coastal locations is usually attributed to insecurity;

as late as 1867 eastern Sphakiotes did not live on the Frangokastello

plain because they feared raids from the sea.19

Churches

But as elsewhere in Greece, churches in Sphakia were

often built outside settlements as well as within them (though never,

as far as we know, above 1000m), and some were built on or near the sea,

where they served as conspicuous landmarks. The only structure definitely

datable to the second Byzantine period is in fact the 10th c. church of

Agios Pavlos on the shore below Agios Ioannis, on the route to Agia Roumeli.20

But as elsewhere in Greece, churches in Sphakia were

often built outside settlements as well as within them (though never,

as far as we know, above 1000m), and some were built on or near the sea,

where they served as conspicuous landmarks. The only structure definitely

datable to the second Byzantine period is in fact the 10th c. church of

Agios Pavlos on the shore below Agios Ioannis, on the route to Agia Roumeli.20

Documents

Other evidence for this period comes from documents.

There is a charter of ca 1184, by which the Byzantine emperor Isaac Angelos

grants or restores the governance and revenues of a territory dependent

on Anopolis to the Skordylis family. This territory is defined by a perambulation,

and its boundary may be roughly determined. The area began near the future

Frangokastello, ran along the N side of the White Mountains, and continued

down to Agia Roumeli. The Anopolis province was therefore much the same

as the modern eparchy of Sphakia, but somewhat shorter at the E and W

ends. The word "Sphakia" is mentioned in the charter, and seems

to have been in use as a geographic term, but was not so precisely defined

as to make the perambulation unnecessary. The 41 place names in the charter

are not those of settlements but of natural features (e.g. Three Olive

Trees). That it is possible to locate a number of these toponyms with

some precision is remarkable, given that nearly 800 turbulent years have

passed since they were recorded.21

Other evidence for this period comes from documents.

There is a charter of ca 1184, by which the Byzantine emperor Isaac Angelos

grants or restores the governance and revenues of a territory dependent

on Anopolis to the Skordylis family. This territory is defined by a perambulation,

and its boundary may be roughly determined. The area began near the future

Frangokastello, ran along the N side of the White Mountains, and continued

down to Agia Roumeli. The Anopolis province was therefore much the same

as the modern eparchy of Sphakia, but somewhat shorter at the E and W

ends. The word "Sphakia" is mentioned in the charter, and seems

to have been in use as a geographic term, but was not so precisely defined

as to make the perambulation unnecessary. The 41 place names in the charter

are not those of settlements but of natural features (e.g. Three Olive

Trees). That it is possible to locate a number of these toponyms with

some precision is remarkable, given that nearly 800 turbulent years have

passed since they were recorded.21

Venetian period

In the Venetian period (1204-1669)

there is some material evidence for the importance of Anopolis and a certain

prosperity in Sphakia generally. Gerola first noted a house with Venetian

features in Anopolis;22 it could have belonged

to the Skordylides. The house is also a indication that the main settlement

of Anopolis was no longer on the ridge where the Graeco-Roman city had

had its centre. No church in Anopolis has yet been dated to the Venetian

period, but at least three churches in the eparchy have 14th c. frescoes

(one at Aradena, two at Agios Ioannis).23

In the Venetian period (1204-1669)

there is some material evidence for the importance of Anopolis and a certain

prosperity in Sphakia generally. Gerola first noted a house with Venetian

features in Anopolis;22 it could have belonged

to the Skordylides. The house is also a indication that the main settlement

of Anopolis was no longer on the ridge where the Graeco-Roman city had

had its centre. No church in Anopolis has yet been dated to the Venetian

period, but at least three churches in the eparchy have 14th c. frescoes

(one at Aradena, two at Agios Ioannis).23

The

economic importance of Sphakia is more clearly revealed in documents of

the Venetian period. In 1463 the Anopolis plain is listed as a major grain-producing

area; 24 again, it is frustrating not to

be able to date the construction of agricultural terraces. Cypress was

a valuable timber of which the White Mountains were an important source

in the Venetian Empire in the 15th c. and later. Some of the 11 sawmills

in the Samaria Gorge observed by us may be Venetian; mills in this area

are mentioned in Basilicata's report of 1630.25

The Skordylis family reappears in two 15th c. documents, in which a murderous

dispute with another Sphakiote family over pasturage for sheep and goats

is to be resolved by a dynastic marriage.26

Sheep were kept for their milk, to judge from a 17th c. traveller's account:27 The

economic importance of Sphakia is more clearly revealed in documents of

the Venetian period. In 1463 the Anopolis plain is listed as a major grain-producing

area; 24 again, it is frustrating not to

be able to date the construction of agricultural terraces. Cypress was

a valuable timber of which the White Mountains were an important source

in the Venetian Empire in the 15th c. and later. Some of the 11 sawmills

in the Samaria Gorge observed by us may be Venetian; mills in this area

are mentioned in Basilicata's report of 1630.25

The Skordylis family reappears in two 15th c. documents, in which a murderous

dispute with another Sphakiote family over pasturage for sheep and goats

is to be resolved by a dynastic marriage.26

Sheep were kept for their milk, to judge from a 17th c. traveller's account:27

The cheese which is made here [i.e. in the White Mountains] is bought

up by the Venetians and other Merchants, and transported to France,

Italy, Zante etc. It is the best cheese that is made in any of the Southern

parts, and generally as good as our own Cheshire Cheeses, being made

as bigg.

Pastoralism

Pastoralism

seems to have been an integral part of the Sphakiote economy at least

as early as the Venetian period.28 It is

tempting to assume that the system of transhumance still practised in

Sphakia--sheep and goats are moved in the summer to the Madhares (high

pastures), where large round cheeses (graviera) are made in the corbelled

huts called mitata--was already in operation in the Venetian period. But

the mitata cannot themselves be dated, and at this altitude (1700-2000m)

there are no churches to provide any chronological peg.29 Pastoralism

seems to have been an integral part of the Sphakiote economy at least

as early as the Venetian period.28 It is

tempting to assume that the system of transhumance still practised in

Sphakia--sheep and goats are moved in the summer to the Madhares (high

pastures), where large round cheeses (graviera) are made in the corbelled

huts called mitata--was already in operation in the Venetian period. But

the mitata cannot themselves be dated, and at this altitude (1700-2000m)

there are no churches to provide any chronological peg.29

All three products mentioned--grain, timber, and cheese--were

for export to Venice. The inhabitants of Sphakiote villages, then, should

not be seen as subsistence farmers and shepherds, but as the productive

subjects of a highly exploitative imperial power. The Venetian yoke did

not always sit lightly on Cretan shoulders, as the insurrections of 1294-99

and 1366-67 reveal; material evidence for trouble in Sphakia comes from

the fort at Frangokastello built in 1371-4.30

All three products mentioned--grain, timber, and cheese--were

for export to Venice. The inhabitants of Sphakiote villages, then, should

not be seen as subsistence farmers and shepherds, but as the productive

subjects of a highly exploitative imperial power. The Venetian yoke did

not always sit lightly on Cretan shoulders, as the insurrections of 1294-99

and 1366-67 reveal; material evidence for trouble in Sphakia comes from

the fort at Frangokastello built in 1371-4.30

Turkish period

Sphakia continued to be rebellious during the Turkish

period (1669-1898). Daskalogianni, who was from Anopolis, led the revolt

of 1770, as a result of which the village was burnt. The peculiar lack

of older, larger olive trees in the Anopolis plain may be the result of

Hüseyin Bey's order of 1824, that they be cut down for his troops'

firewood.31 At least 9 new forts were built,

some commanding good views of the coast (even at the cost of being difficult

to maintain or reinforce; e.g. the forts at the mouths of the Trypiti

and Samaria Gorges).

Sphakia continued to be rebellious during the Turkish

period (1669-1898). Daskalogianni, who was from Anopolis, led the revolt

of 1770, as a result of which the village was burnt. The peculiar lack

of older, larger olive trees in the Anopolis plain may be the result of

Hüseyin Bey's order of 1824, that they be cut down for his troops'

firewood.31 At least 9 new forts were built,

some commanding good views of the coast (even at the cost of being difficult

to maintain or reinforce; e.g. the forts at the mouths of the Trypiti

and Samaria Gorges).

Sphakia,

like much of Greece, has the remains of a remarkable network of carefully

constructed mule tracks. They are called kaldirimia (from the Turkish

kaldirim) but we have as yet no evidence for their date of construction.

The main route into Sphakia was through the Imbros Gorge where there are

remains of a broad, well-paved kaldirimi; Pococke travelled on this road

in the 1740s.32 Lesser tracks (but even

the narrow ones paved and provided with steps) connect all the villages

and cultivated areas, and run even into the Madhares and the Trypiti Gorge. Sphakia,

like much of Greece, has the remains of a remarkable network of carefully

constructed mule tracks. They are called kaldirimia (from the Turkish

kaldirim) but we have as yet no evidence for their date of construction.

The main route into Sphakia was through the Imbros Gorge where there are

remains of a broad, well-paved kaldirimi; Pococke travelled on this road

in the 1740s.32 Lesser tracks (but even

the narrow ones paved and provided with steps) connect all the villages

and cultivated areas, and run even into the Madhares and the Trypiti Gorge.

The

only monastery known so far in Sphakia, that of Agios Kharalambos, was

built right on the coast of the Frangokastello plain (E of the fort) circa

1835.33 Other structures of the Turkish

period include the Kankellaria at Loutro, built in 1821, which housed

the Revolutionary Committee.34 The

only monastery known so far in Sphakia, that of Agios Kharalambos, was

built right on the coast of the Frangokastello plain (E of the fort) circa

1835.33 Other structures of the Turkish

period include the Kankellaria at Loutro, built in 1821, which housed

the Revolutionary Committee.34

CONCLUSIONS

After two seasons of field work, the Sphakia Survey has located (or

relocated, in some cases) 98 sites, of which 34 have a prehistoric phase

(35%); and 67 have a Graeco-Roman phase (69%). We surveyed 5 km2 in 1987,

and 10 km2 in 1988.

Connections

As for our broader objectives, we have learned a great deal about Sphakiote

connections with the outside world. In the prehistoric period, the presence

of obsidian and a particular pottery fabric suggest links with (respectively)

the Aegean (probably Melos), and the NW coast of Crete. The scarcity of

Classical-Hellenistic black glazed pottery contrasts sharply with the

surprisingly wide distribution of Samian ware. Similarly, the material

culture and documentary evidence of the Byzantine, Venetian, and Turkish

periods suggests that "remote" Sphakia was integrated into the

economy of Crete and beyond.

Settlement patterns

We can also draw some tentative conclusions about preferred locations

in different periods, to be tested in our next field season. The few Final

Neolithic/Early Minoan sites discovered so far are all in the area of

Anopolis and Aradena, i.e. at about 600-800m. Later in the PH period,

however, people lived on the coast at Loutro and also in the plain from

Khora Sphakion to Frangokastello. Tarrha, the only Archaic site known

to date, is also a coastal settlement. But Classical and Hellenistic material

tends to be found away from the sea; Poikilasion is a good example. Under

the Romans, occupation continued at many inland sites, such as Anopolis

and Araden, but the main settlement at Poikilasion seems to have shifted

to the foot of the Trypiti gorge. By the late Roman/first Byzantine period,

there were many coastal settlements, the most notable of which was probably

Loutro, with a number of smaller sites in the Frangokastello plain. But

for most of the second millennium A.D., people lived in inland villages,

up to 1000-1100m.

Future field work in Sphakia will be carried out in environmental zones

not intensively sampled so far (the Madhares; the Askyphou and Frangokastello

plains), with continued revisiting of other areas; by the end of our third

season we hope to have surveyed a representative sample of the eparchy.

Work can then begin on the final publication of the Sphakia Survey, which

will incorporate environmental, archaeological, documentary, and ethnographic

evidence.

LUCIA NIXON, QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY/CANADIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF WOMEN,

JENNIFER MOODY, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA

SIMON PRICE, LADY MARGARET HALL, OXFORD

OLIVER RACKHAM, CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

FOOTNOTES

1. Permission to conduct the survey was obtained from the Archaeological

Council of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sciences, through the

Canadian Archaeological Institute at Athens. The Faculty of Arts

and Sciences, and the School of Graduate Studies, Queen's University,

made an exceptional grant to cover two student fares; Moody's fare

was paid by EEC funding for the Desertification of Southern Europe

project. Price's expenses were covered by a grant from the Craven

Committee, Oxford University; Attwell's, by a grant from the Mediterranean

Studies Program, Rice University. Additional funding came from Dr

E.H. Keay. The video camera and recorder were lent to the project

by the Language Teaching Centre, Oxford University. We are most

grateful to all these individuals and institutions for their support

of the project. We would also like to thank the staff of the Khania

Ephoreia, Stavroula Markoulaki, Maria Andreadaki-Vlasaki, Vanna

Niniou-Kindeli, and Elpidha Khatzidhaki; the Geographic Service

of the Greek Army; Dr Jacques Perreault, Maria Tolis, and Eugenia

Atzitiri, CAIA; and, for all their help in Sphakia, Khrysi and Thodori

Athitakis; Mikhali and Georgia Athitakis; G. Douroudou; and the

Paterakis family. Our team consisted of two archaeologists (Nixon,

Moody); a botanist (Rackham); a historian (Price); five cheerful

and hard-working students, four from Queen's University (Julie Clark,

David Marko, Meryn Scott, Catherine Woolfitt), and one from Rice

University (Chapman Attwell).

|

back |

2. See L. Nixon, J. Moody and O. Rackham, "Archaeological

Survey in Sphakia, Crete," EMC/CV 32 n.s.7 (1988) 159-173 (with

map of the eparchy).

|

back |

3. W.S. Hanson and P.A. Rahtz, "Video Recording on Excavations,"

Antiquity 62 (1988) 106-11. Video has been used elsewhere on Crete;

see J.A. MacGillivray, L.H. Sackett, J. Driessen, and D. Smyth,

"Excavations at Palaikastro, 1986," BSA 82 (1987) 136.

|

back |

4. Caves at Asphendou: A. Zois, "A propos des gravures rupestres

d'Asfendou (Cr?te)," BCH 97 (1973) 23-30, and Kapsodasos: E.L. Tyree,

Cretan Sacred Caves: Archaeological Evidence, PhD diss., University

of Missouri (1974), 48-50. Frangokastello: S. Hood, "Some Ancient

Sites in South-West Crete," BSA 62 (1967) 53. Loutro: S. Hood, "Minoan

Sites in the Far West of Crete," BSA 60 (1965) 113. Mesolithic:

see Nixon et al. (above, n. 2) 162, 173. Late MInoan III pots: Hood,

BSA 60 (1965) 113.

|

back |

|

5. Drapanias and Nerokourou, M. Andreadaki-Vlasaki, pers. comm.;

Akrotiri, J. Moody, "The Development of a Bronze Age Coarse Ware

Chronology for the Khania Region of West Crete," Temple University

Aegean Symposium 10 (1985) 51-65 and The Environmental and Cultural

Prehistory of the Khania Region of West Crete: Neolithic through

Late Minoan III, PhD diss., University of Minnesota (1987).

|

back |

6. Poikilasion is the best attested form of the name. The alternative,

Poikilassos, is found only in the late Stadiasmus maris Mediterranei

(330-1); if this form is ancient it belongs along with other names

ending in -ssos which indicate pre-Greek presence.

|

back |

7. Tzedakis, in Davaras, "Dutiki Kriti," ADelt 26.2 Khron (1971)

511. For Geometric material from elsewhere in West Crete see M.

Andreadaki-Vlasaki, "Geometrika nekrotapheia sto nomo Khanion,"

Pepragmena tou E' Diethnous Kritologikou Sunedriou, 2 vols (Herakleion

1985) i.10-35.

|

back |

8. Dittenberger, Sylloge 3 627.7-8; revision of Delphic inscription

by P. Faure, "Epigraphai ek Kritis", KrChron 21 (1969) 327-32. Apollonia:

B.F. Cook, Inscribed Hadra Vases in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

(New York 1966) no.1, with J. & L. Robert, "Bulletin ?pigraphique,"

REG 80 (1967) no.662.

|

back |

9. SEG 8.269.

|

back |

10. H. van Effenterre, La Cr?te et le monde grec de Platon ? Polybe

(Paris 1948) 120-60.

|

back |

|

11. Poikilasion: In 1988 we found a column drum possibly from

a temple on the saddle below Profitis Ilias; an inscription records

a temple to Serapis (M. Guarducci, Inscriptiones Creticae (Rome

1935-50) [hereafter IC ] II.xxi.1 = L. Vidman, Sylloge inscriptionum

religionis Isiacae et Sarapiacae (Berlin 1969) 100 no.172, 3rd century

A.D.).

|

back |

12. There is however gold from a grave at Araden: R. Pashley,

Travels in Crete (London 1837) II 256-7.

|

back |

13. P. Brul?, La piraterie cr?toise hell?nistique (Paris 1978)

148-56; I. F. Sanders, Roman Crete to the Arab period (Warminster

1982) 30-31; cf. E. Kirsten, Das dorische Kreta (W?rzburg 1942)

80-86 and A. Petropoulou, Beitr?ge zur Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsgeschichte

Kretas in hellenistischer Zeit (Frankfurt am Main 1985) 133-134.

|

back |

|

14. O. Rackham, "Ancient Landscapes," in O. Murray and S. Price

(eds.), The Greek City, from Homer to Alexander (Oxford 1989) 85-111.

|

back |

15. Names: Aituros, Eukrine, Tharsutas, Protogenes, Serambos,

Taskomenes, Teimonenes; also Margulos, peculiar to Anopolis and

Tarrha. We are grateful for the assistance of Elaine Matthews of

the Lexikon of Greek Proper Names, Oxford.

|

back |

|

16. Vase: J.N. Svoronos, "Attiki hydria ek Kritis," Journal international

d'arch?ologie numismatique 4 (1901) 457-469 (now in Athens, NM 1443).

|

back |

17. Phoinix: IC II xx 8 = Vidman (above, n.11) 99 no.171 (A.D.

102-114).

|

back |

18. E.S. Lambrinakis, Geographia tis Kritis (Rethymnon 1890) 53-63;

I.E. Noukhakis, Kritiki Khorographia (Athens 1903) 218-228; P. Faure,

"Villes et villages de la Cr?te occidentale. Listes in?dites 1577-1644,"

Kritologia 14-15 (1982) 77-104, at 83-84.

|

back |

19. T.A.B. Spratt, Travels and Researches in Crete. 2 vols (London

1865) II.428.

|

back |

20. J.E.H. Skinner, Roughing It in Crete in 1867 (London 1868)

197; in this case the fear was of Turkish raids. The one town in

our area, Khora Sphakion, stands in the protection of its Venetian

castle, although even here the older houses are not directly on

the coast; G. Gerola, Monumenti veneti nell'isola di Creta (Venice

1905-1932) I.257. The port hamlet of Loutro is another exception

to the rule, but it was traditionally inhabited chiefly in winter

and may have grown up only after it, too, was provided with a castle

at some time in the Turkish period.

|

back |

21. Gerola (above, n.20) vol. III.266 fig. 166, 268.

|

back |

22. K. Gallas, K. Wessel and M. Borboudakis, Byzantinisches Kreta

(Munich 1983) 256-257. The church of Prophitis Ilias above the Trypiti

Gorge has two shallow brick domes and may also date to this period.

|

back |

23. E. Gerland, "Histoire de la noblesse cr?toise au moyen age,"

Revue de l'orient latin 10 (1903) 172-247, 11 (1908) 7-144; S. Xanthoudidis,

"To diploma (provelegion) ton Skordilon Kritis," Epetiris Etaireias

Kritikon Spoudon 2 (1939) 299-312.

|

back |

24. Gallas, Wessel and Borboudakis (above, n.22) 253-256.

|

back |

25. S.G. Spanakis, Symboli stin istoria tou Lasithiou kata tin

Benetokratia (Heraklion 1957) 17.

|

back |

26. A.P. Bourdoubakis, "Anekdota kritika engrapha ek Sphakion,"

Epetiris Etaireias Kritikon Spoudon 2 (1939) 256-262.

|

back |

27. B. Randolph, The present state of the islands in the Archipelago

(or Arches) (London 1687) 85.

|

back |

28. B. Randolph, The present state of the islands in the Archipelago

(or Arches) (London 1687) 85.

|

back |

29. For earlier types of pastoralism, and for discussions of the

integration of pastoralism into economic systems, see C.R. Whittaker

(ed.), Pastoral Economies in Classical Antiquity, PCPS 14 (1988).

Note also that sheep were important in the Bronze Age economy of

Crete, but for wool, not milk; cf. J.T. Killen, "The wool industry

of Crete in the late bronze age," BSA 59 (1964) 1-15.

|

back |

30. Women and children seem never to have accompanied the men

and their flocks to the Madhares; the absence of churches (and ikonostasia)

is perhaps a symbolic indication that the high pastures have never

been part of the civilised world of family life.

|

back |

31. For the construction date of Frangokastello, see M.G. Andrianakis,

""To Frangokastelo Sphakion," Arkhaiologia 12 (1984) 72-80. And

the well-known Cretan song mentioning the Omalo plain ("Potes tha

kami xestergia...") definitely belongs to the Venetian period; see

G. Morgan, "Cretan Poetry. Sources and Inspiration. ch. 1. The Folksongs,"

KrChron 14 (1960) 9-68 at 25-29.

|

back |

32. Pashley (above, n.12) II.243.

|

back |

33. R. Pococke, A Description of the East and some other countries

(London 1745), vol. II.1, 240-241.

|

back |

34. Andrianakis (above, n. 31) 78-80.

|

back |

35. S.G. Spanakis, Kriti. 2 vols (Herakleion n.d.) vol.2, 252.

|

back |

|